Throughout humanity's history, we have conceived of various gods and goddesses, the majority of which are now either lost to history or relegated to myths and history books.

Mankind, sensing their estrangement from the Divine, crafted various idols and symbols. Thus, he conceived in his mind forms, forms which were used to help him with various aspects of life so that mankind could more effortlessly work with the Natural world.

In their book The Sword and the Serpent, Denning and Phillips describe how early humans began to populate their environment with powerful symbols:

“Just as man covered the walls of his caves with pictures and began shaping fragments of bone or rock into figurines, so he began to fill the delicate Astral world about him with shapes of dominant force: Great Bison to command the bison, Great Bears to command the bears, Men to befriend him or to give commands in his name, and the Woman who was mother and bride and daughter. Man’s understanding became greater; deduction fortified intuition. He imagined gods for himself, and those images tool walked the Astral.”

Denning and Phillips further suggest that "those forms created by man which possess sufficient strength and sephrotic purity become real conduits."

Every culture may conceptualize a unique deity that, if imbued with sufficient spiritual purity, can become a vessel for a more profound, ethereal energy.

This helps explain why certain myths and symbols endure through the ages; they resonate with higher, archetypal forces.

The form is inferior to the idea which takes on the form. In other words, it’s the concept which is behind the form that resonates with a deeper part of ourselves.

It’s why there are “timeless” symbols that persist across various cultures. It’s not the symbol that is timeless, but the idea behind the symbol that is.

We utilize symbols to express ideas. Language, for example, is a form of symbolism, where combinations of letters and sounds act like incantations, animating the concepts they signify.

Different cultures employ unique symbol systems that, when deciphered, reveal the mental frameworks of those cultures.

Philosopher Alan Watts captures the essence of this relationship, stating:

"Words and magic were in the beginning one and the same thing, and even today words have the power to cast spells."

Symbols are ways in which higher ideas can be born. By interpreting the symbol, we can successfully bridge the gap between the ethereal and the concrete, allowing the higher to become grounded in physical reality.

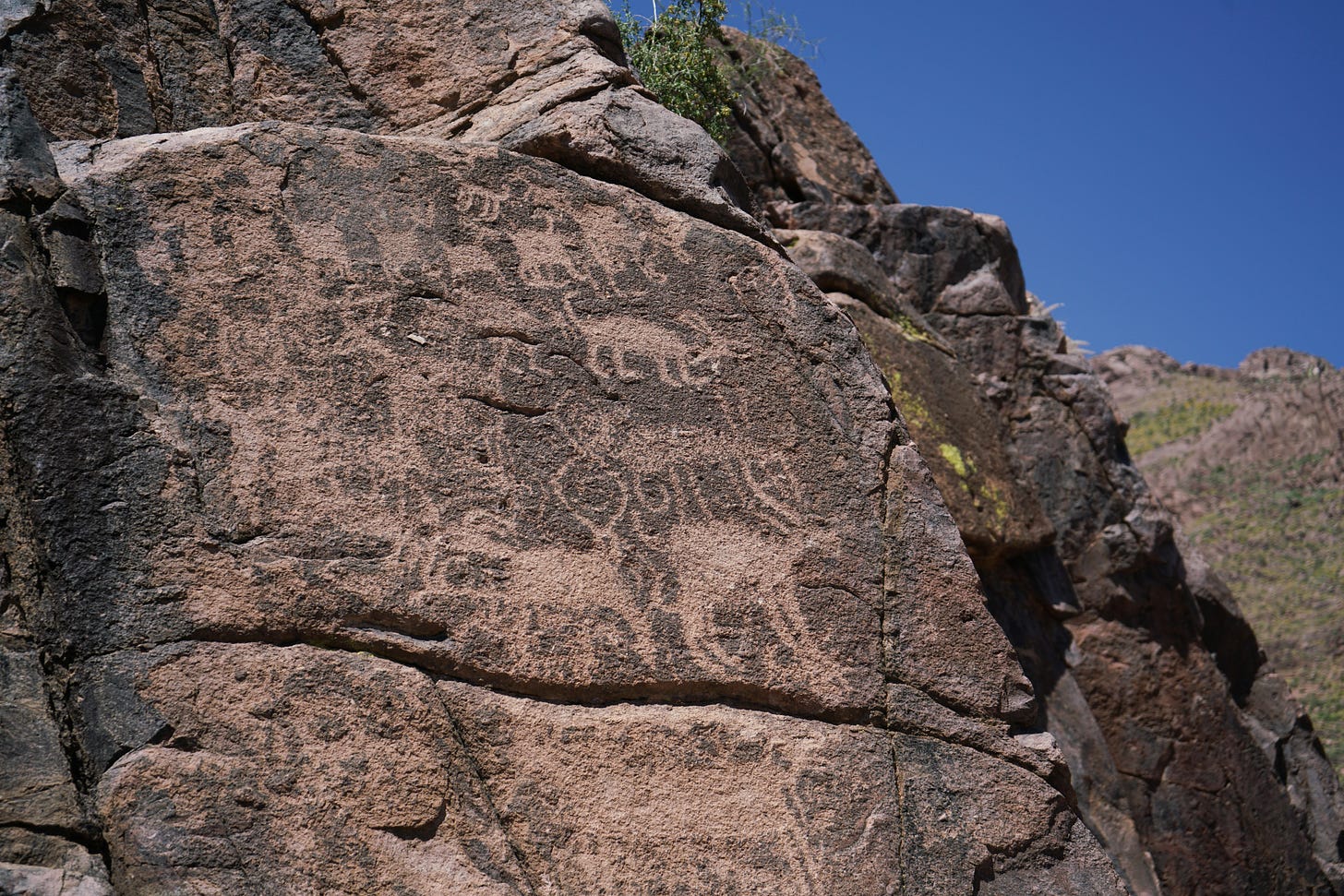

In the American Southwest, various cultures etched symbols onto rocks all over the region. Unfortunately, many of these cultures are lost to history and we can only guess what the symbols they left behind mean.

By attempting to interpret the symbols, we can gain a greater understanding not only of the culture, their cosmogony and world outlook, and the archetypal forces they sought to engage with. This exploration allows us to connect with a broader human experience, linking us across time to the profound mysteries these early peoples contemplated.

The Hohokam culture, which thrived from around 300 AD to 1500 AD, was one of the largest Native American settlements in the Southwest, centered in what is now Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona. The surrounding mountains in Phoenix are adorned with numerous petroglyphs they left behind.

The Hohokam are a bit of a mystery. We do know that they existed from approximately 300AD to 1500AD and set up one of the largest Native American settlements in the southwest. We also know that in order to live in the harsh deserts, they developed extensive irrigation systems that supported large agricultural endeavors.

Additionally, they possessed a deep knowledge of astronomical phenomena, aligning their activities and possibly their beliefs with the movements of celestial bodies.

They are believed to have origins in Mesoamerica, which encompasses modern-day Mexico and Central America.

In Phoenix, near Superstitious Mountain, there is a site called “Petroglpyh Spring” that contains numerous petroglyphs which I recently had the opportunity to visit.

What became immediately apparent when I arrived at the site was that this area had a strong aura of power and was indeed very special to the Hohokam.

I believe this area may have served as a ritualistic site where shamans sought to directly engage with their gods. They might have conducted rituals to invoke rain and/or harness the power of thunder for their magical practices.

This interpretation aims to explore the possible spiritual beliefs the people in this area may have had and is, therefore, highly subjective.

I acknowledge that these are speculative insights and do not claim them as definitive truths. Nonetheless, I find them interesting enough to share.

To begin, it should be noted that Superstitious Mountain is steeped in folklore, including tales of supernatural occurrences and legends such as the Lost Dutchman, which are well-known among the Apache and Pima Native American tribes.

The mountain was considered by native peoples in the area to be the dwelling place of the Thunder God, a belief that seems plausible when visiting Phoenix during the monsoon season.

The area is known for dramatic lighting displays during the rainy season and boosts an unusual number of lightning strikes. This has contributed to the area’s mystical and sometimes ominous reputation.

Getting to the spring requires a short, 2-mile hike through the open desert and once in the spring, you are immediately greeted by the many petroglyphs etched on the basalt outcrops.

You also notice that it is particularly fertile and rich in diverse plant, flower, insect, and reptile species. To the Hohokam, natural springs were regarded as places where the Divine and the Earth meet and it's evident why they would believe this when you first arrive.

The contrast between this verdant, lively area and the harsh desert environment just a short distance away is striking.

The very first group of petroglyphs you come to appears to be a depiction of a herd of animals, possibly antelope.

In my opinion, this is erroneously thought to be a sign of fertile hunting grounds. Although antelope are often associated with fertility, I believe the intent behind this petroglyph was to evoke the roaring sound of thunder, which closely resembles the rumble of a stampeding antelope.

There are other petroglpyhs of antelope and deer around the spring, however, I did not find a large group of them like this. And to be placed at such a prominent place at the entrance suggests its significance.

Below the herd of antelope are a few petroglyphs that depict an image of frogs. In Mesoamerican culture, frogs and toads are linked with Tlaloc, the rain and storm god. They are also seen as the musicians or voices of the Maya rain god, Chac, and feature in myths regarding the origins of fire among humans.

Interestingly, the southwestern native Shamans also viewed deer as mediators between heaven and earth and their prominent depiction above the frogs may also indicate an attempt to gain the assistance of the deer spirits during their rituals to the Thunder God at this site.

Moving further along, we come upon another small group of petroglyphs which appear to depict a circle with two dots and a wavy line extending downwards as well as a coyote.

According to author Heike Owusu, wavy lines were symbols that represented the "energy that builds matter," encompassing both physical and spiritual energy.

The symbol of a circle with two dots is sometimes interpreted as representing Death.

And in many Southwestern native cultures, the coyote is viewed as a trickster figure, known for its cunning and resourcefulness. It is also sometimes associated with chaos and disruption.

There's a popular Native American myth that echoes the Western story of Prometheus, involving the Coyote who steals fire. This tale, with its variations, is found across many Native cultures, including the Hohokam.

In this story, Coyote, known for his cunning and trickery, sees that humans have fire, which they use for warmth, cooking, and protection. However, Coyote doesn't have fire himself and desires its benefits. He schemes to steal fire from the humans.

Coyote first attempts to trick the humans into giving him fire, but they refuse. Then he devises a plan to steal fire while the humans are sleeping. He approaches their camp cautiously and carefully takes a burning stick from their fire, planning to carry it back to his own camp.

However, as Coyote is sneaking away with the stolen fire, he accidentally sets his own tail on fire. Panicked, he tries to put out the flames, but in doing so, he inadvertently spreads fire to other parts of the world, including to other animals and plants. Eventually, fire becomes available to all living beings.

In some versions of the story, Coyote's actions lead to chaos and destruction, while in others, they lead to the enlightenment and empowerment of all living things through the gift of fire.

This cluster of petroglyphs might be conveying a message about destruction or death, ultimately leading to a form of "rebirth."

Alternatively, the petroglyphs could serve as a caution, highlighting the dual nature of fire—as a force that can both destroy and sustain life.

Moving ahead to the next rock, we come upon an interesting grouping of petroglyphs that appear to depict lighting.

If we interpret all three groups of petroglpyhs together, this could be telling a dramatic story demonstrating the generative power of lighting.

Behind the visible site of lighting and the audible sound of thunder is the creative work of the Gods. This work is the work of Creation, of life giving, of manifesting.

However, to give life also means an aspect of life must die. Therefore, Creative Fire burns as well as enlightens.

Therefore, to the Hohokam, lightning must have been viewed as a Creative Force which, if harnessed, had the power to create and destroy.

On the opposite side of the spring, you won’t find as many dramatic petroglpyhs, however, there appears to be an abundance of anthromorph figures, likely related to the shamans performing the ritual. One in particular caught my eye.

This figure is standing with arms bent and a line runs from between its legs. Above its head is an arch.

This one stands out as truly unique and must hold some significance.

To interpret this, we should look at the influence of the Mesoamerican cultures, particularly in the three main religious and ideological principles that influenced the native americans of the Southwest. Author David Carrasco identified them as: 1. world making, 2. world centering, and 3. world renewing.

World-making, recorded in mythologies about how the universe was made, expressed the organization of society by and around ceremonial centers modeled after the structure of the universe.

World-centering related concepts of the universe to the human body and was expressed through the performance of ritual specialists.

World renewing was a ceremonial rejuvenation of time, human life, agriculture, and the gods organized according to astronomical and calendrical events.

In my view, this is representative of a “world-centering” concept.

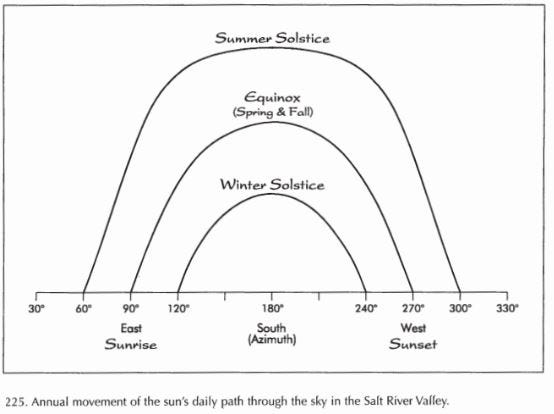

In researching this particular petroglyph, I came upon this image in the book Landscape of the Spirits, by Todd Bostwick and Peter Krocek.

The image depicts the annual movement of the sun’s daily path through this region. Curiously, it matches the shape of the arch seen above the humanoid figure.

The Hohokam, known for their sophisticated astronomical observations, might have intended this image to represent the path of the sun during key solar events like the Winter Solstice, and the Spring and Fall Equinoxes.

Notably, during the winter and early spring months, the spring beneath this petroglyph is at its fullest,

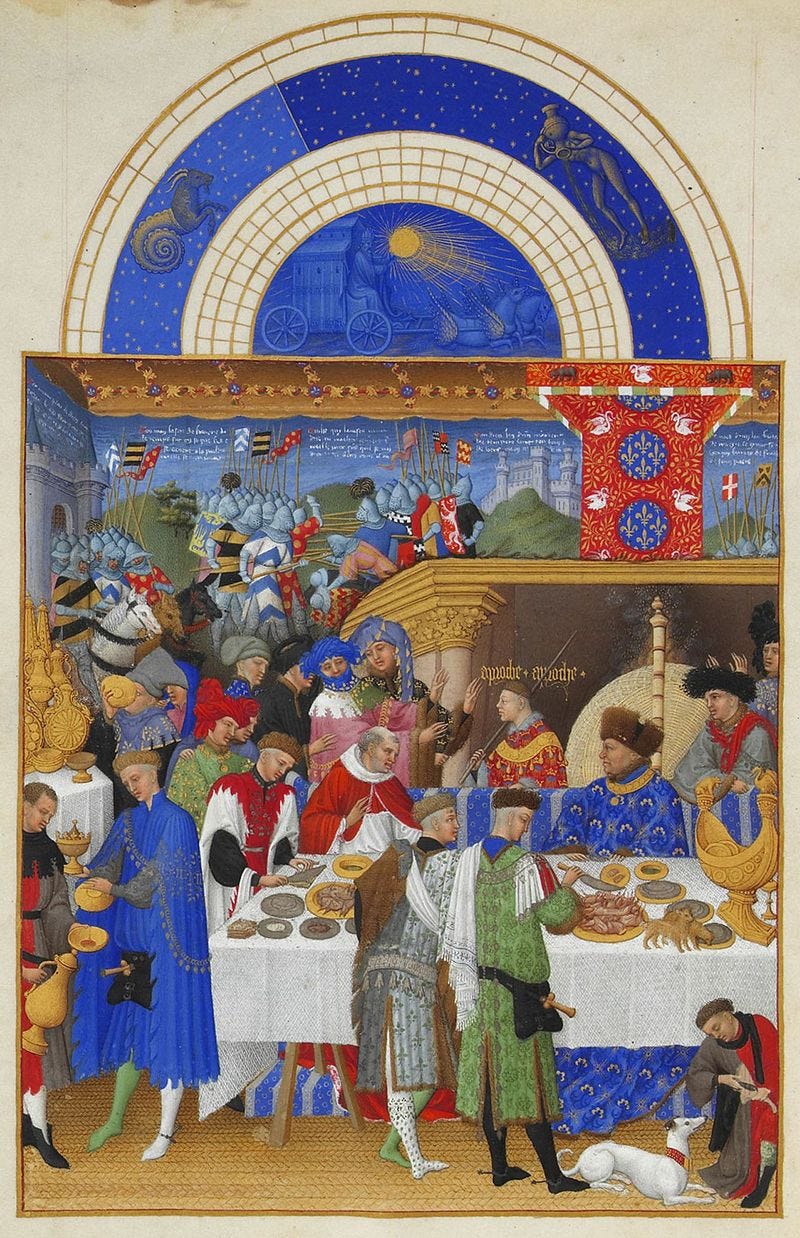

Another interpretation might view the arch as symbolic of a halo or the sun itself. In Western symbolism, an arc, since it is a fragment of a circle, is symbolic of the life force, of the potential spirit. It is also associated with the moon, the feminine force that seeks union with the masculine.

Archs are commonly used to represent the spiritual world or the heavens.

From The Book of Hours of the Duc de Berry.

If the arch symbolizes the cosmos, then the figure of the man positioned beneath it could represent the "grounding" point for cosmic energy.

The posture of the man, with his arms at his waist and a long line extending downwards from between his legs, might depict the concept of "grounding."

This petroglyph possibly illustrates the role of humanity in channeling celestial power from the heavens through themselves, serving as conduits between the sky and the earth.

To gain a fuller understanding of this petroglyph's meaning, it's useful to examine the petroglyph immediately to its left. This adjacent image features a circle with a dot in the center, from which a line extends with two arms projecting upwards.

The circle and dot motif, frequently used by the Hohokam, is commonly believed to be associated with the moon. This linkage suggests a celestial interpretation, possibly emphasizing the moon's significance in the transmission of cosmic energies.

However, the symbol on the left is more than just a circle with a dot; it also features a vertical line extending downward and a horizontal line bending upwards.

This configuration brings to mind the Tau Cross or the Ankh from ancient Egypt. Frederick Goodman discusses the Tau Cross in his book Magic Symbols:

“The upright line is sometimes interpreted based on its position relative to the horizontal or feminine line. For example, when the upright line hangs from a vertical line, it is said to symbolize the creative ray (vertical) emanating from the maternal womb (horizontal)—the human spirit emerging from the female.”

This symbol could represent the descent of the spirit (vertical) from the maternal womb (horizontal) of a higher spiritual realm (circle).

Considering that the Hohokam used the circle and dot to symbolize the moon, they may have viewed the moon as a portal to the spiritual realm. Thus, invoking the moon could be seen as a way to draw spiritual forces down to the material world.

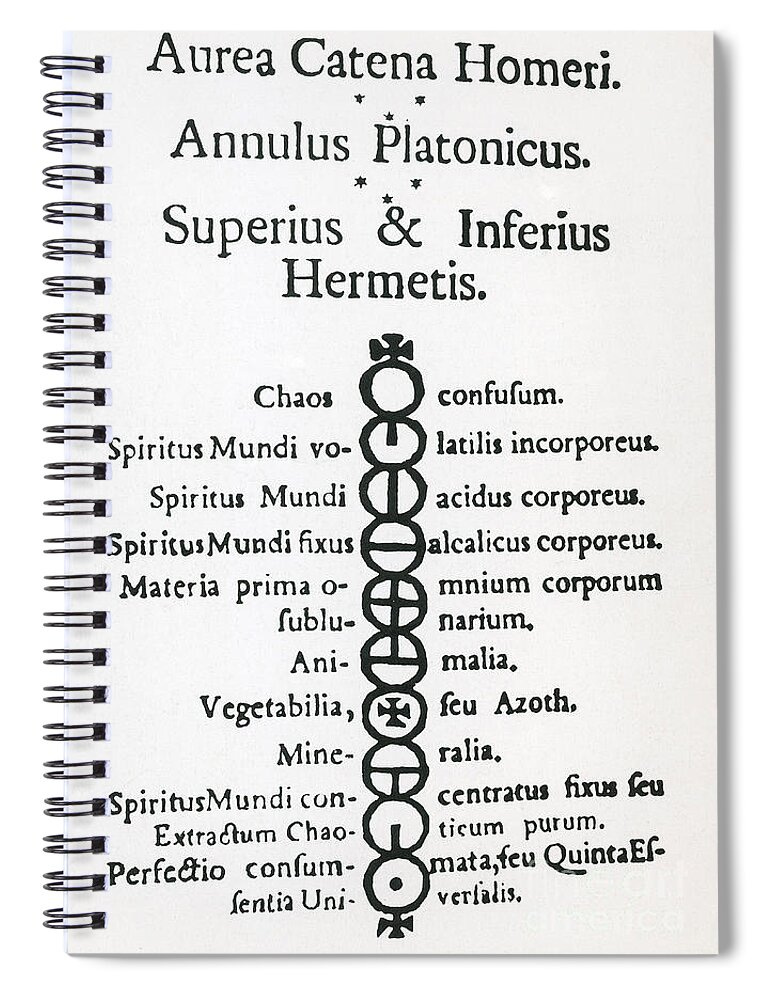

Interestingly, we can see a similar shape in the image The Golden Chain of Homer (1757), where a circle with a dot followed by a cross appears at the bottom of the chain. This configuration is meant to be read downwards, with the last circle symbolizing the Divine.

In this context, the vertical line represents spiritual power, while the horizontal line suggests material opposition.

What's particularly intriguing in the petroglyph is the upward bend of the vertical line, which could symbolize a return to the heavens.

If the image on the right suggests mankind "taking" celestial power, then the image on the left might represent mankind returning that power to Heaven after its purpose has been fulfilled.

This petroglyph likely depicts the ultimate result that Shamans were looking for - to bring down “fire” from Heaven and then to return it.

This petroglyph appears to be depicting a coyote and possibly a rattle. A rattle is sometimes used to depict the sound of water or rainfall. Evoking water may be an attempt to evoke the “waters of creation”.

One of the interesting things you will notice about all the petroglyphs found in the Phoenix area is that almost all of them are etched onto Basalt rocks.

The South Mountains are formed of mostly Basalt, which is a type of volcanic rock rich in magnesium and iron.

Many argue that the prevalence of petroglyphs on basalt stems from two main reasons: firstly, basalt is abundant in areas where petroglyphs are commonly found, and secondly, the rock's darker outer layer provides an ideal surface for carving. This darker surface allows the etched designs to stand out more clearly once the petroglyphs are completed, making them more visible and distinct from the lighter inner rock.

While this is true, I believe that the Hohokam chose Balsalt specifically because of the magnetic qualities that Balsalt exhibits when it is struck by lightning.

The origins of the Hohokam, along with many other Southwestern Native American groups, are deeply connected to Mesoamerica. This link is supported by the discovery of numerous Mesoamerican artifacts at Hohokam archaeological sites, indicating a history of trade and cultural exchange between the Hohokam and Mesoamerican civilizations.

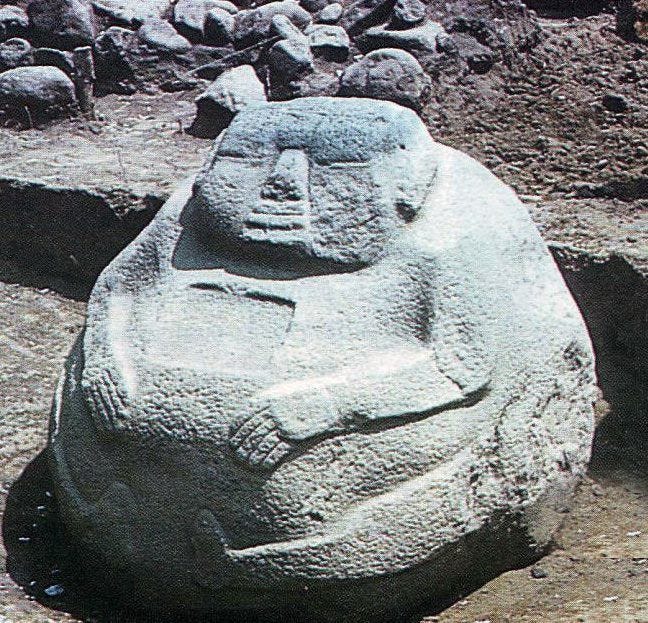

Knowledge of magnetism was known among native Mesoamerican cultures, famously demonstrated by the “Fat Boys of Guatemala”, a series of ancient statues featuring a round human-like figure.

In 1976, archeologist Vincent Malmstrom and his assistant, Paul Dunn, held a compass close to one of the "fat boy" statues and discovered that the compass needle deviated from true north and pointed towards the stone.

Upon testing other statues and giant heads at the site, they observed that the needle was strongly attracted to specific parts of some statues—namely, the navel on some and the right temple on others. The magnetic force emanating from the stones was significantly more intense than the Earth's own magnetic field.

It is believed that these statues were intentionally crafted from rocks with high iron and magnesium content, such as basalt, which may have been struck by lightning.

In the American Southwest, archaeologists have found that many petroglyphs were intentionally etched onto rocks that had been struck by lightning and have demonstrated that these rocks exhibited magnetism. Similar findings have been observed with petroglyphs in other parts of the Americas, including Wisconsin.

Petroglyphs etched on magnetized rocks also appear on petroglyphs found in other parts of the Americas such as Wisconsin.

Native peoples considered carefully what type of rock that the petroglyphs was to be drawn on.

Petroglyph Spring was clearly a significant site for the Hohokam people, and its special nature is evident to anyone who visits. The Hohokam shamans likely used the right side of the Spring, when facing the mountain, as the “stage” to perform their rituals and the left side as the altar which represented the forces they wanted to evoke.

(view looking away from the mountain)

The forces that the Hohokam shamans sought to communicate with were closely tied to the life-giving properties of Fire.

Their rituals were likely designed to enhance the potency of their magic. I believe that these practices were not solely for practical outcomes, such as evoking rain, but also aimed to harness the power of Fire to enlighten and expand the understanding of the shamans themselves.

The idea was to metaphorically "bottle" lightning, using its potent energy to boost their magical efforts.

The South Mountains around Phoenix are a very powerful place magically and it’s easy to see why Native peoples considered these mountains sacred.